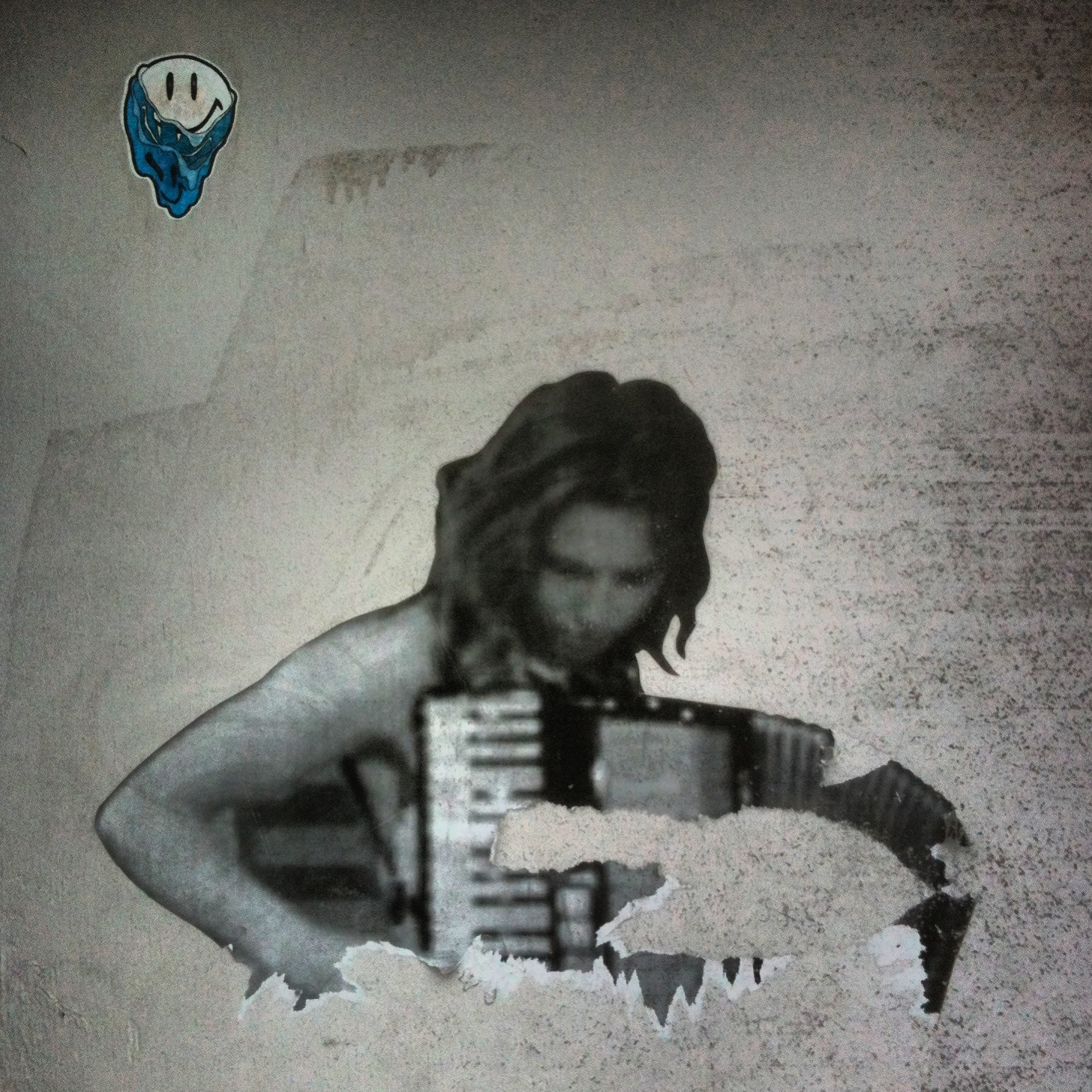

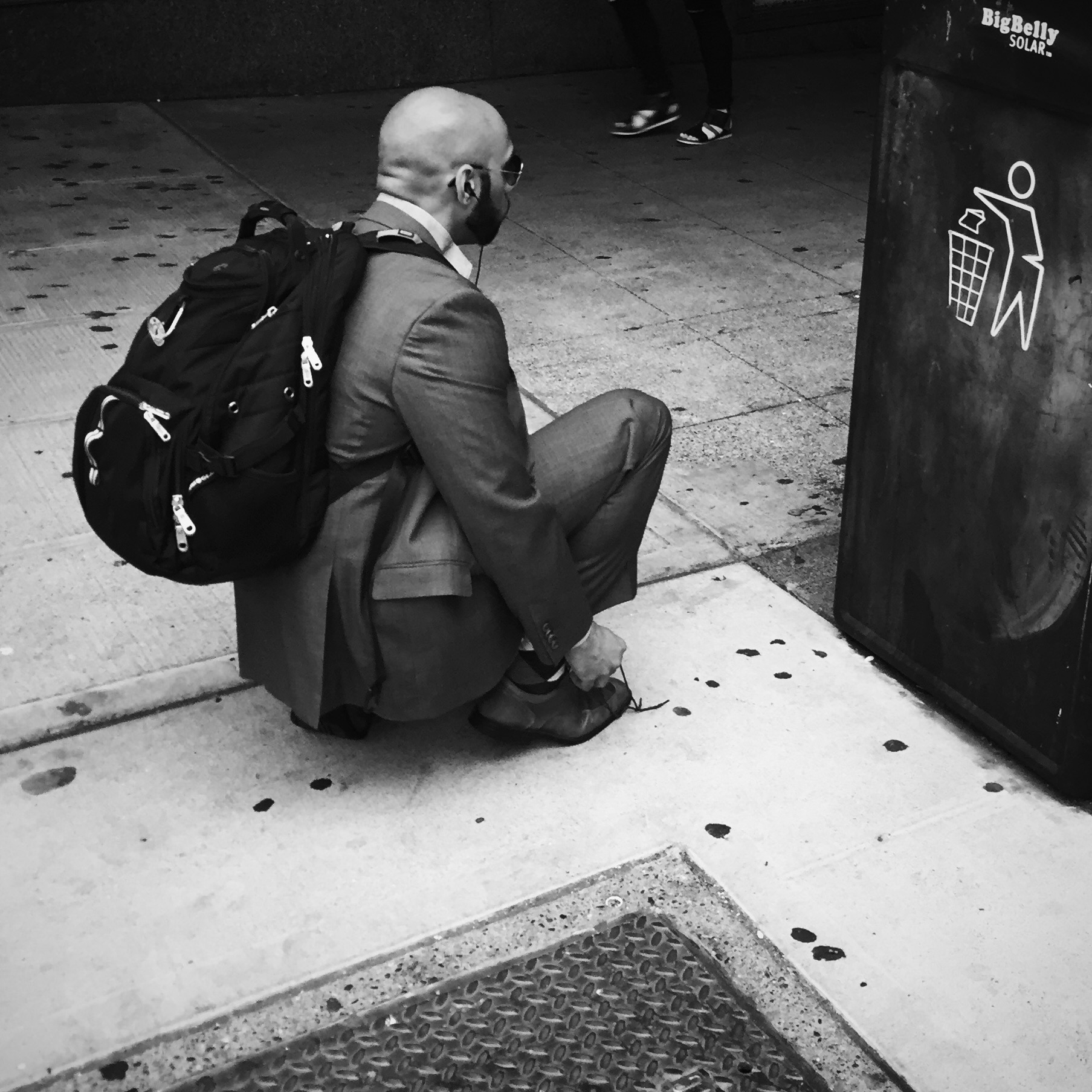

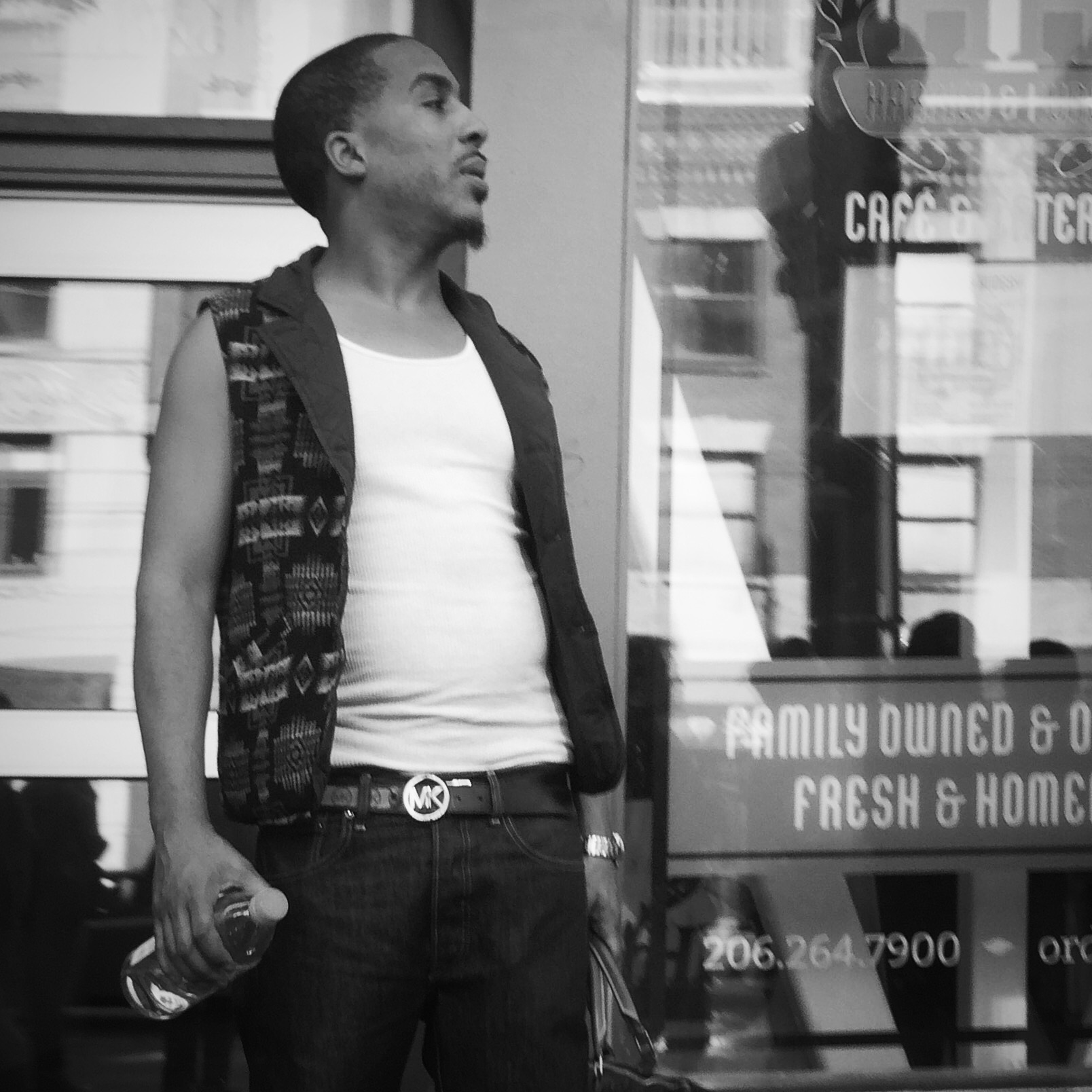

Museum Guards

black and white prints, medium format

Once upon a time, I was a security guard at the Seattle Art Museum. I had just gotten out of grad school and moved to Seattle, and figured that being around the art would be a great way to start a career. Apparently I wasn't the only one thinking along these lines. Just about every guard I met was an artist of some sort; there were painters, photographers, musicians, actors, writers - all of us hoping to "move up" by getting our foot in the door.

Maybe we thought we would be discovered and given an exhibition. Maybe we thought we would end up assisting a curator. In the tradition of actors who wait tables, we were artists guarding art.

We walked. And walked. And walked. Once the excitement of looking at the art faded, the monotony set in. "Where's the bathroom?" Down the hall to the right. Excuse me, please don't touch the art. Thank you. For people who wanted so much to be a vital part of the art community, we were essentially anonymous.

The great thing about this, though, was the sense of comradery that grew among many of us. Someone was always doing something, having a show, recording an album, etc. I began to realize that this group of people was in many ways so much more vital than the institution in which we worked, and I wanted to document it.

Fortunately, I lived less than a block away from the museum. This made it easier for me to convince my co-workers to come over during lunch breaks and have their pictures taken. Breaks were only half an hour, so if I had more than one or two volunteers on any given day, I had to work fast.

The setup was pretty simple - I had a white wall, a medium format camera and a couple of lights with umbrellas. Each guard stood against the wall and posed however they liked; I wanted to capture each person's personality unadorned by props or stilted poses.

This approach is nothing new in photography. Although this plain backdrop look has become common in advertising, I was at the time thinking more along the lines of artists like Disfarmer, Richard Avedon and Chuck Close. These people let their subjects speak for themselves, in a way that was respectful and truthful.

I had no way to develop my photos. Fortunately, the then-Curator of Prints and Photography at the Seattle Art Museum, Rod Slemmons, took an interest in the project and offered to develop my film for me.

With generous support from Allied Arts of Seattle, I was then able to make prints from the negatives Rod developed for me.

John Kieltyka